Do you like Paul Lewis?

Posted: Sun Jan 09, 2011 9:59 pm

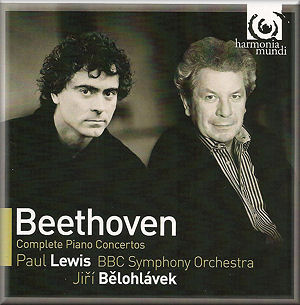

I bought a CD set of his Beethoven Piano Concerto cycle with the BBC SO and it is truly wonderful. This extract is from today's Observer.

Paul Lewis: 'Schubert writes something that comes from another planet'

Paul Lewis is about to set off on an epic world tour. But what were the chances of a Liverpool docker's son from an unmusical family becoming the finest British pianist for generations? Here he talks about falling for classical music as a child at his local library – and why we need to listen again to Schubert

Paul Lewis was 13 years old when his father, Ken, was laid off from his job as a docker for the port of Liverpool. These were the mid-1980s, a hard time on Merseyside, where the deindustrialisation of Britain took an especially ruthless toll in an Atlantic city built proudly upon shipping and shipbuilding. Lewis had been born and raised in the outlying community of Huyton (eight years older than a neighbour – and also master of his craft – called Stevie Gerrard). For a while, Lewis's mother, Theresa, was the family wage-earner, keeping down a job at the housing benefit offices of Knowsley district council.

The schoolboy Lewis had, though, by this time already chosen his path in life, and there was nothing the ravaging of Liverpool could do to stop him. Since the age of eight, he had been making visits to the local public library to borrow albums of the music he had discovered all of his own accord, and come to love and understand: that of Beethoven, Mozart – and Schubert. Days and evenings poring over spinning vinyl, and tape-recording the classical repertoire, were the beginnings of a career that has made Paul Lewis the most illustrious and talented British-born pianist for generations. This year Lewis crowned nearly a decade of intensive concentration on Beethoven's music to become the first pianist to perform all the piano concertos at a single season of the Proms, and released an acclaimed box set of them, following a set of the sonatas.

Now, Lewis turns his attention to the work of the quintessential romantic figure, who himself adored Beethoven: Franz Schubert. Lewis's plan to perform Schubert's late piano music is an epic one: a tour begins in February in Southampton and over two years will encompass the UK, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Austria, Switzerland, Ireland and Japan and Australia. There will be concerts in scores of places and the entire cycle will be performed in 15 cities, including London, Liverpool, Oxford, Bristol, Perth, New York, Chicago, Tokyo, Melbourne, Rotterdam, Bologna, Florence and at the Schubertiade in Schwarzenberg. "Ten years ago," Lewis reflects, "I played a Schubert sonata cycle across six venues in the UK, then the whole thing in France. That was something crazy – but if that was crazy, what's this!?"

The tour will focus on solo piano works Schubert wrote during the six years between 1822 – the year he was diagnosed with syphilis, "after which everything changes completely in his music", says Lewis – and his death in November 1828, with the three last great sonatas as the tour's eventual kernel. Its most poignant engagements for different reasons will be eight homecoming performances at St George's Hall in Liverpool over two years.

"It was an unusual way to start a life with music," reflects Lewis, when we meet in a coffee bar near his home in Chesham outside London. "It was all me – going to the library round the corner, taking out the three LPs I was allowed, taping them illegally, returning them and getting three more. At first, I expected everyone to feel like I did. There was a moment listening to that opening of Beethoven's Fourth, when the thing just TAKES OFF – dadada, dadada – dadaVROOOOM-dada…! – I called over to my mother and said: 'Listen to THIS!' and she did, and said: 'What? Oh, yes, lovely,' and I felt like shouting, 'No, Mum! It's, it's – like nothing else in the world!'"

Lewis's musicality may have come from nowhere genetic, but it was implanted during infancy. "When I was four, an aunt gave me a toy organ, an octave and a half, and I'd write and play my own tunes." The music in the house, he says, "was John Denver… My parents were never anything other than supportive but didn't themselves know about music, and had nothing to guide them, which was both an advantage and a disadvantage".

Lewis's primary school had no piano teacher, "which is why I started by learning the cello, at which I was not good at all". At the age of 11, Lewis's parents arranged for him to try for a place at the independent Chetham's school of music in Manchester, up the East Lancs Road. He was turned down, "so I went to the local comp, which was OK, but there were no kids interested in the same sort of things as me". His talent had been spotted at Chetham's, however, by a piano teacher, Nigel Pitceathly, who took Lewis on. "So that every Wednesday, my father" – who was by now working in a special needs school – "would drive me to Stockport for a lesson, which was quite a thing for him to do." It paid off: aged 14, Lewis was accepted by Chetham's, and his course decided. "For the first time, I was surrounded by people who shared my interest, who I could talk to about music, and that saved me, I suppose." Saved him from what? Lewis laughs: "I never got to find out what exactly I was saved from." After leaving school, Lewis was admitted to the Guildhall School of Music, and in 1994 was runner-up in the London International Piano Competition.

Now 38 years old, Lewis is disarmingly agreeable to talk to, utterly without pomposity, attentive and alive to whatever discourse is in hand and passionate about his subject, which he discusses with the same erudite transparency – devoid of airs and graces – that is the hallmark of his playing. His timbre and sonority are crystalline, direct, intense and deeply emotional but free from theatricality and impetuosity. He is more faithful to a score than many, and one feels while listening to him play as close as is possible to a direct communication with the intentions of a composer. This is by design, and essential to Lewis's notions of his performances and his own stardom. "Sometimes, I go to a concert and what I notice is the performer more than what they are playing. I see them putting on a show – I understand it, and there are people who do that, but it's not what I try to do. It's too easy for it to become all about the performer. Yes, it's wonderful to walk on to a stage and have everyone applaud, and applaud again when I've finished. But that is not what this is about. It's not about me, it's about the composer and the music, and the message of the music, the feelings and emotions it is trying to convey. The music is more important than me…

"This is the music I love, and my hope is that the people who come and hear it can love it too. That the experience will be long-lasting – and if it is, it will be because of Schubert."

Lewis and I meet on an afternoon when Chesham is the coldest place in Britain. Getting there entailed a hike through a blizzard from the nearest functioning station at Amersham, thus affording a silly joke from me, arriving late, about Schubert's song cycle Winterreise (Winter Journey). The date was 18 December, and Lewis suddenly remembers something: exactly two years ago, we were both in Vienna (with separate parties) for the unforgettable experience of Alfred Brendel's valedictory concert, so we shake hands and raise paper cups-full of coffee in tribute to the master. For me, that had been a heart-stopping farewell to an idol I had never met; for Lewis, it was more than that. As a child, among the library records Lewis would borrow and tape were recordings by Brendel, "so I knew his playing before I met him. I'd been inspired by the sound he made". When Lewis became Brendel's pupil after leaving the Guildhall, "it was astonishing to see at close quarters what he was doing. We talked about his ideas and the sounds he was trying to achieve; for me, that was when the light went on, and it's still there. It was all about message – yes, we talked about use of the pedals, different timbres and colours, but you can talk about sonority and technique until you're blue in the face – the real point is how to get the message across. With someone like Schubert, there are many layers, many things being said at the same time, shedding different light. The tricky thing, the point, is to get the delicate balance that conveys the message – and Alfred was the master of the message."

There is gratifying connectivity in all this: Brendel, who was the first pianist to record Schubert's entire oeuvre for keyboard, was one in a line of champions of the composer since his death, beginning with Robert Schumann recovering unperformed and unpublished work from the garret in which Schubert died, aged 31. The mantle of many colours that Brendel passes to Lewis generally, he now does specifically with regard to the great Viennese composer who came to be called, on account of his short stature and wild frizzy hair, "Schwammerl", ("little mushroom").

Franz Schubert is the archetypal bohemian artist, the romantic's romantic. Unlike any of the major composers who worked in Vienna during the Classical and Romantic periods, Schubert was the only one actually born in the Hapsburg imperial capital, son of a schoolmaster and musician. It is essential, says Lewis, to get away from the "old stories" about Schubert, first of all, "those of the shy schoolmaster who wouldn't say boo to a goose", let alone the figure of the libertine Schubert was supposed to have become.

"It's too interesting and complicated for all that," says Lewis. "We should start with the fact that this is a man of very deeply felt emotions who found that the best way to convey what he felt was through music. It is elusive, multi-layered and complex, but there's also something immediately understandable about it – Schubert is unusually clear about his understanding of things, and the way he feels. He is strong in himself, even if the life he led was shy and retiring."

Lewis's point underpins important scholarship on Schubert, markedly a biography by Christopher Gibbs, who posits that for all the fact that only a fraction of Schubert's music was published during his lifetime, and even less of it performed – thus creating the posthumous figure of the "rejected" bohemian genius – Schubert had a "fierce awareness of his artistic genius and worth. For too long," argues Gibbs, "his shyness has been confused with low self-esteem".

Of course, the myth is propelled also by Schubert's circumstances and private life. His music was mostly performed at 'Schubertiade" evenings of music, drinking and dancing with friends and his devoted immediate circle of students, bohemians and political radicals opposed to the stifling repression of Metternich's Austria (Schubert was himself arrested for subversion). Schubert's romantic and sex life have long fascinated posterity: there have been treatises on his possible homosexuality, and he does appear to have much preferred sexual relationships "on the side" with working-class girls – a chambermaid called Pepi Pöckelhofer in particular – than ladies of his artistic circle. Meanwhile, his passions were famously and unrequitedly reserved for such figures as his aristocratic pupil Countess Caroline Esterházy, who was beyond his reach and yet also associated with the creative spells that produced his greatest music. The countess once complained that Schubert dedicated no work to her, to which her teacher replied: "What's the point? Everything is dedicated to you anyway."

Dualities of sorrow and joy – and a calibration of sentiments in between – entwine and juxtapose with unique intensity in Schubert's music and, argues Lewis "in Schubert's very elusiveness lies the point of intense communication. We want to identify with the person behind the music, and with Beethoven and Mozart this is less complicated. With Schubert, it's all much hazier."

There are descriptions of Schubert having "drunk too much" on numerous occasions, and smelling heavily of tobacco; his use of opium is speculated upon, but not authenticated. One of his friends, Wilhelm von Chézy, noted that "when the juice of the vine glowed within him, he did not bluster… but liked to withdraw into a corner and give himself contentedly to silent rage". Schubert's appearance was unkempt, and he suffered bouts of depression – pursued, says his friend Eduard von Bauernfeld, by "a black-winged demon of sorrow and melancholy" – disappearing from his circle for long periods that could also be his most astonishingly productive.

"When I think of Schubert on the basis of the music itself, I don't think of him as gruff, but rather as a man of great tenderness and intimacy," Lewis reflects. "Everything is on a smaller scale than Beethoven; he is not in search of the big effect, but something more graded and intimate. This is something I came to realise during the last sonata cycle 10 years ago, and wanted to return to, after so many years with Beethoven".

Schubert is often said to have lived and worked in the shadow of the man he adored and whose gale-force influence was unavoidable in early 19th-century Vienna: Beethoven. Although they died within two years of each other, Schubert was a generation younger than the great genius, and there exist tantalising accounts of their possible meetings: one is said to have occurred when Beethoven was on his deathbed in 1827, but evidence of the encounter cannot be substantiated. Certainly, Beethoven's death left a legacy, which history credits Schubert as having taken on, and which Schubert may even have continued consciously during the 20 months he outlived his hero. After all, while Beethoven's work was performed and acclaimed during his lifetime, it was only after Beethoven's death that the (relatively) impoverished Schubert got even his best work presented in public. There's a famous story: after attending Beethoven's funeral, Schubert and some friends drank until late at a tavern, where a toast was made to the lost genius, and to whomsoever would follow him next – which in the event was Schubert.

After six years playing Beethoven and almost only Beethoven, however, Lewis has a striking view on his musical relationship to Schubert. "I never take much notice of Beethoven's shadow so far as Schubert is concerned," he says. "A lot is made of the influence, but what strikes me are the differences rather than the similarities." Differences that demonstrate Schubert's originalities, and which militated against his professional career: as Percy Young writes in the definitive study of Schubert's piano music, "Schubert's originality was against him. He could write neither pseudo-Beethoven nor simple diatonic sonatas in the style of early Haydn."

"We're all supposed to think that the Viennese Classical era produced one tradition of music," says Lewis. "But no: Beethoven always seems to find a way to find a way through, even to triumph. Schubert never does. He never finds a solution. At least, not after 1822 when he was diagnosed with syphilis. Everything then changes in the music – it becomes so bleak."

So it is by contrast to, rather than comparison with, redemptive Beethoven that Lewis explains his Schubert: "There is no piece like Schubert's middle A minor sonata in Beethoven, nothing so bare, so sparse: long unharmonised passages, a repeated two-note figure going through the piece… there is stark resignation, rather than a will to win through." In the C minor sonata, he says, "We have been on this journey, and we've seen things along the way, but there is no accumulated wisdom – it has no end, there is no way out, we are still there." The A major sonata D959 "ends with a movement that is 12 minutes long, as though he is wanting to work and re-work these ideas with as much time as he has got left, like stolen time – the coda, so resigned, as if saying goodbye for the last time. But there is no sense of 'I'll be all right.'" Schubert knew he was dying; in an important letter to his friend Leopold Kupelwieser, he said his "most brilliant dreams have perished". And with his sonata in B flat, says Lewis: "Schubert writes something that comes from another planet. I'm not a religious person at all, but it is something beyond…" – Lewis leaves his point hanging in the cold air, both his voice and his cup of coffee giving off steam, snow against the cafe window. "As though it's, well, after all our troubles, this is what comes next."

One of Schubert's hallmarks – crucial to this posthumous legacy – was the number of "unfinished" masterpieces he left, not least the famous "Unfinished" Symphony and the glorious, two-movement "Reliquie" piano sonata that forms part of the first round of Lewis's two-year tour. Schubert deployed, writes Gibbs, "a compositional process that made him abandon magnificent pieces", and scholars have debated whether this was because Schubert wrote opening movements so extraordinary they led to impasses (as Gibbs suggests), or because he had no patron or publisher, let alone performance contract.

Lewis, though, adds the compelling notion that, like Michelangelo's great "unfinished" statues of prisoners wresting their way free from blocks of stone, these pieces are every bit as "finished" as Schubert intended them to be. "They are extraordinary as they stand," says Lewis. "The 'Reliquie' is the most difficult of all to play – not physically, but in terms of message: it is a piano redaction of an unfinished orchestral score, much of it un-harmonised, so you have to realise the implied symphonic harmonies; there are colours you have to realise. The second movement has a mix of menace and a sense of dance; maybe Schubert just felt there was nothing significant to add, and left the piece as it was. But then, there's another piece in F sharp minor that is also made of two movements, and this time maybe Schubert thought he just didn't have enough material to develop them in the same way as he did other pieces."

Prolific Schubert was apparently unable to take a break from his creative urges. How does Paul Lewis wind down? "I wish someone could explain to me how it's done," he smiles, and to look at his Schubert schedule for the next two years, this elusive "someone" will not be presenting themselves to him any time soon. "I have three young children and spend my time with music – so between those things, life is busy enough. I've just had to accept that I can't put in the hours I have to for my pilot's licence. And I do try to make a point of staying tuned, aware of what is going on in the world. What's happening to education – to the libraries, indeed, and I should know what they're worth! – it's all so depressing, isn't it? But it's been a full-on year for me, with all this to come, and there've been times when I've felt it."

Happily, despite the "depressing" landscape of education in Britain, and the march of mediocrity that defines postmodern society, a defiance abounds that endeavours both to spread "classical" music into social, economic and cultural quarters unaccustomed to it, and to reclaim the great composers beyond the elites and establishments. The New York Theatre Workshop has just completed a highly successful run for a play trying to do just that for Schubert, called Three Pianos, which recreates a Schubertiade in and for the East Village, three actors performing and in part adapting the Winterreise cycle while drinking and debating the meaning and nature of music, art and life.

"It's so important," says Lewis, "to define figures like Schubert, just as it's important to reach people who would not otherwise listen to his music. I don't like the term classical music – call it great music, serious music. There's no substitute for having great music around children, but it's easy to go through life without ever really hearing it. It just needs some experience, or someone, to light the candle. Then one can go through all phases of life – whether it's not earning any money or too busy to stop – once that candle is lit, it lasts a lifetime."

For details of UK and worldwide dates, see paullewispiano.co.uk